How Australian fencing left its mark at Sydney 2000

The Australian Fencing Federation (AFF) had been consulted as part of the bid process and was confident it could stage an Olympic event. Bill Ronald, Australian Olympic fencer, sports administrator and coach, was AFF President at the time and suggests the community’s confidence was perhaps naive. “It’s a bit like having your first child,” he says. “You don’t know all the complexities you’re going to have to deal with. We found out later we had no reason to be so confident. It was an extremely hard job.”

Once the Games had been secured, the Sydney Organising Committee of the Olympic Games (SOCOG) engaged Bill to run the fencing event following an open recruitment process. He was one of only a few competition managers to hail from the sport’s national federation. Bill later recruited Sydney coach and fencing equipment supplier Jeff Gray, an expert in technical operations, to assist.

The lead up

Australian fencing had experience in running world cups, having hosted Challenge Australia, first in Melbourne and later in Sydney in the lead up to the Games. But hosting an Olympic event was “immensely different” Bill says.

As part of their preparation, SOCOG sent Bill and Jeff to the 1996 Atlanta Games as observers. “Atlanta had done a good job of design and setup but there were functional problems,” Bill says. “Observing at Atlanta allowed me to look at all the bottle necks, all the bits where there were failings and aggravations – the sharps,” he says.

Bill also spent a week at IBM’s headquarters in Madrid, Spain, to test-run the scoring and timing. IBM custom designed the competition software and scoreboard display for the Sydney Olympics, and every possible variation of a fencing score, including black cards and withdrawals, had to be programmed and tested.

It was during a quiet moment in the stands at Atlanta, watching confusion and congestion in the fencing hall, when the two Australians hatched a novel plan for fencing in Sydney. Perhaps inspired by the Olympic rings themselves, Bill and Jeff devised a tournament based on colour and circular flow. They reimagined fencing as a spectacle played out across red, blue, yellow and green quadrants, making it easier for audiences to follow the action and reducing confusion for competitors.

Coloured pistes, now standard at large international fencing tournaments, introduced by Australia at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games (Supplied/ Bill Ronald)

“Everything in that area would be designed around colour – the score boards, the piste surrounds, the athlete boxes,” Bill says. “The colours would create sectors which didn’t require language or special knowledge of the sport.”

“It would also make things easier for the athletes and their support staff,” Jeff adds. “If an athlete was going to be competing on the red piste, then they would prepare on a red piste in the warm-up hall and sit on the red chairs in the staging area.”

The Australians also settled upon circular movement for competitors entering the main arena, ensuring incoming athletes and officials didn’t cross paths with those exiting the playing field. For back-of-house, they engineered a predictable cycle for athlete preparation, taking them from check-in with officials to a dedicated warm-up piste with a training partner, coach and medical assistant. From warm-up they’d move to equipment control, then to athlete marshalling. This cycle would be repeated for every round of every event.

The Venue

Before they could put their plan into action, fencing needed a home. This proved a challenge. In the 1998 ABC television series The Games, a mockumentary about the Sydney Olympics, episode 10 involves the organising committee realising it’s “one venue short”. Bill maintains the fictional dilemma was based on the real life experience of fencing.

“For ages we didn’t have a venue,” Bill says, as the Olympic Coordination Authority (OCA), responsible for finding and in some cases building facilities for all the sports, struggled to find a fencing arena. The OCA proposed the Hordern Pavilion, but line-of-site animations requested by Bill demonstrated fewer than half the spectators would be able to see the action if it moved from centre stage, so it was ruled out. Other suggestions included Canberra Stadium and a hangar at Richmond Airforce base. The FIE wanted Sydney Olympic Park. “None of these were suitable,” Bill says.

He ultimately persuaded everyone Darling Harbour was a better place to be, securing two halls at the exhibition centre with the cooperation of Boxing, which relinquished half a hall for the first week of competition. The venue proved a key to the fencing tournament’s success, as sharing a location on the city’s doorstep with popular sports volleyball and wrestling attracted large crowds from nearby offices.

Creating a spectacle

Australians had run fencing world cups prior to the Sydney bid, but these were very simple events by comparison. “I was scared to death about running the Games,” Bill says. “So we went into every single detail. It was staggering.”

Bill was the grand master, a puppeteer pulling levers and pushing buttons across a vast motherboard to ensure fencing delivered the goods for athletes, spectators, and the IOC. Jeff engineered the events themselves, relying on South Australian fencer and coach Leon Thomas to supervise the field of play and organise athletes for presentation before bouts.

The tournament comprised epee, foil and sabre events for men and epee and foil for women, with between 36 and 44 athletes in each. Timing was tight, with an entire event run on each of eight days and “the now famous day six” holding two – “a day from which Leon Thomas is still recovering,” Bill says.

The Sydney Games amped up the staging and presentation to make fencing more spectacular. The pageantry that’s now standard for World Fencing Championships and Olympic events was revolutionary in 2000. Every event was on a 20-minute cycle that had to be staged with presentation, music, and march on.

Coordinating the television schedules added an extra layer of complexity. In one instance, the organisers were castigated for starting a final five seconds early, forcing European broadcasters to interrupt a major soccer final. Despite this, the Sydney Games were hailed a success in promoting fencing, with many nations televising every bout fought by their athletes.

“One of the key things we did was to have an ordered event,” Bill says. “From the opening round, all athletes were assembled with their weapons pre-controlled. Pre control meant referees didn’t have to worry about weight and gauge at the piste. At the scheduled time the fanfare would sound, and all the athletes and referees marched out in the right order, with their equipment held in weapon boxes coloured according to their piste, and announced according to the piste colour they were on and whether they were to the left or right,” he says. “Leon organised it all.”

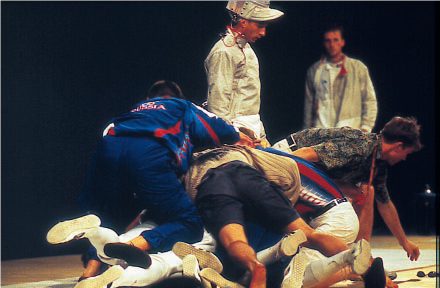

Leon Thomas quietly at work in the background, removing a dropped pair of glasses from the field of play as the Russian men’s sabre team celebrate clinching gold at the Sydney 2000 Olympics (FIE)

“What happens on the field of play is absolutely critical. Leon and Jeff took care of that,” Bill says. “At the same time, we had dozens of scoring and timing staff rostered in flights who needed lunch. The athletes’ lounges needed their drinks machines filled, fruit bowls topped up, ice and fresh towels supplied,” he says. Bill employed Cate Purcell, “a brilliant young organiser”, to recruit, train and roster the huge volunteer staff needed to deliver on these details.

Bill says his job was to walk, watch, worry and fix. “We were determined to make Sydney ‘the athletes games’, one the athletes admired,” he says. “Everything we did was to achieve that.”

Sometimes this commitment to athletes showed in small moments, like Jeff finding a secret door for those who needed to get outside for a smoke. Other challenges were more complex, like a scheduling conflict which threatened to relegate an epee teams match for minor placings onto the warmup piste. Jeff wouldn’t have it, pushing back, convincing Bill with a proposed switch around that risked delaying the final and medal presentation.

To make the change, Jeff and Bill had to negotiate with the venue, the ticketing staff and the presentation team, but they pulled it off. “It was mind-numbing,” Jeff says. “It was a risk, but I’d calculated a timeframe that the teams match could be done in. So, these guys got to fence, 7th and 8th, as they should, at the Sydney Olympic Games, on the coloured piste in front of a crowd.”

Writing about the Sydney Games for the FIE journal Escrime International, Jean-Marie Safra reports “Sporting equality and a sense of theatre—those were the two golden rules which dominated the Games in Sydney.” He recounts the long ovation given to the Chinese épéeists, who did a lap of honour when they won the bronze medal, which he says “stemmed from the same pleasure shared”.

The devil is in the detail

Bill and Jeff worked full time for SOCOG for two years in the lead up to the Games, and in Bill’s case even longer as a part-timer. They planned for every imaginable contingency, including the unthinkable. “I had to know where the nearest hospital emergency room was and how to get an athlete there in the event of a life-threatening injury, like a serious puncture wound,” he says. “Because if an athlete died during combat then the venue would be declared a crime scene and the whole event would have to be shut down.”

While that dramatic scenario did not eventuate, there was a moment of panic when FIE officials arrived for final inspection and declared the lights in the finals hall would be in the athletes’ eyes. But Bill and Jeff had done their ‘what if’ planning and had this scenario covered. “We called in two athletes from the Athletes Commission, who jumped up on stage and put masks on,” Jeff says. “They moved up and down for a bit, then took their masks off, gave us a thumbs up and walked away.” Problem averted.

Despite the team’s meticulous planning, not everything panned out as expected. “There were issues with transport,” Bill says. A carefully considered bus schedule for 14 daily services between the athletes’ village, the fencing training centre in Glebe and the competition venue in Darling Harbour proved to be wishful thinking. “Not one bus ran on time.” Bill says.

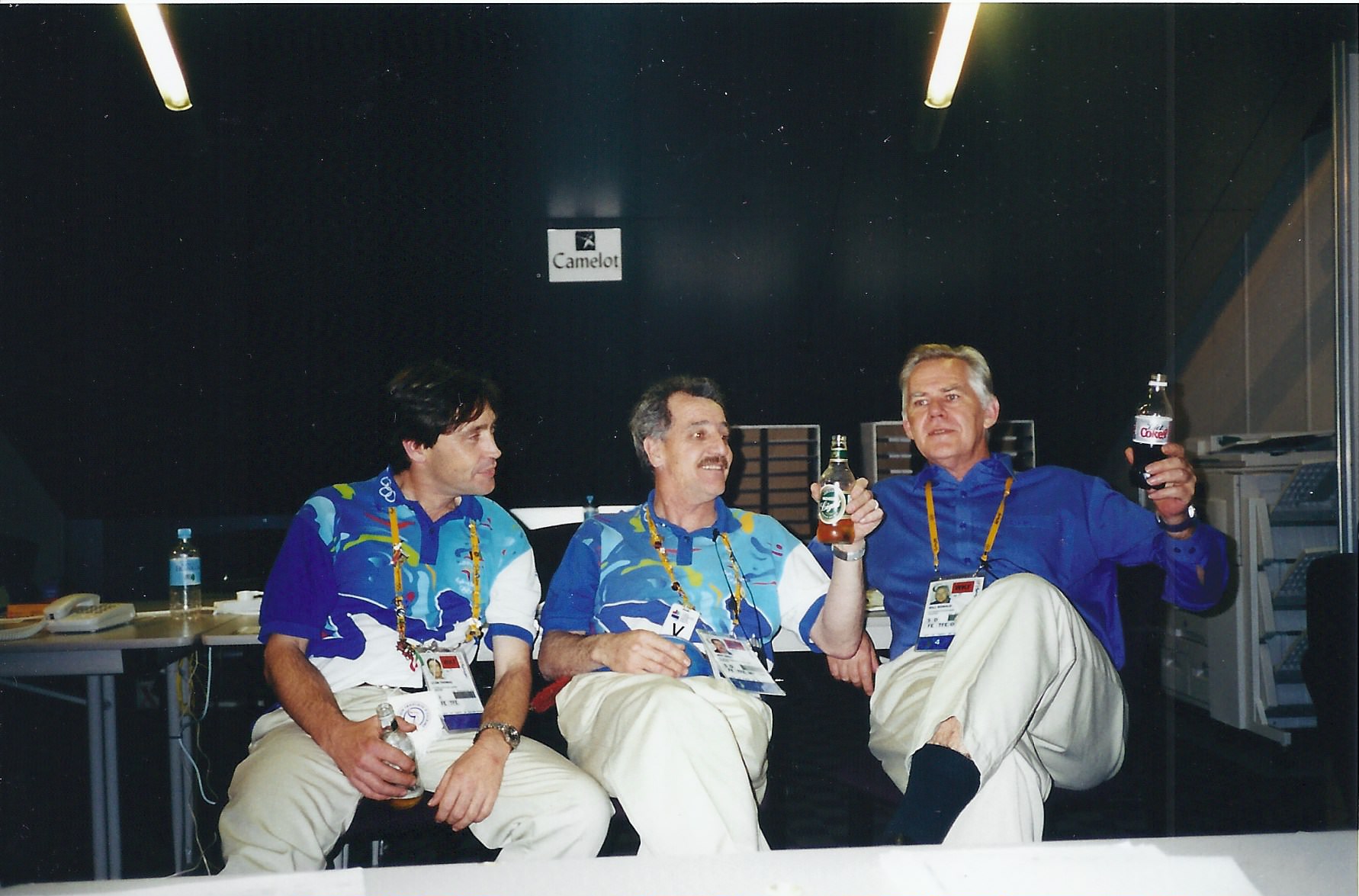

Sydney 2000 Fencing Sport Information desk with (L-R) Alex Donaldson, Andrew Ius and volunteers

(Supplied/ Bill Ronald)

Bill had appointed Andrew Ius, a long-standing executive with Fencing Victoria and later AFF President and “a consummate administrator”, as Sport Information and Transport Manager. But not even Andrew could control the buses.

“You need several thousands of bus drivers for the entire Games,” Bill says, “of whom only some are local. The rest have no idea where they’re going.” Instead, Andrew ignored the timetable and simply ran the buses constantly, sending a bus on its way as soon as people waiting at a stop had boarded, receiving full marks from appreciative athletes as a result. “They gave us gold stars for our transport,” Bill says. “Mind you, it did involve Andrew having to buy the entire Spanish team tapas one day because the bus just didn’t come.”

Team Effort

Sydney 2000 Olympics Australian Fencing Team

Back (L-R): Nick Heffernan, Gerald McMahon, Evelyn Halls, David Nathan, Luc Cartillier,

Front (L-R) Alwyn Wardle (foil coach), Vlad Sher (epee coach), Joanna Halls, Gerry Adams, Helen Smith (team manager)

(Supplied/ Bill Ronald)

View details of the Australian fencing team for the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games here.

While athletes and coaches who represented Australia at the Sydney Games have added a special notch to their fencing totem poles, another team can count the tournament as a highlight of their respective careers. Three Australian referees – Tony Dapre, Peter Osvath and Garrison Liu – earned a blazer as an official. Denise Dapre was a member of the Directoire Technique, appointed by the FIE, and Alex Donaldson ran the results system, working closely with James Fazekas (former High Performance Manager of Australian Fencing) who ran results for IBM for the tournament.

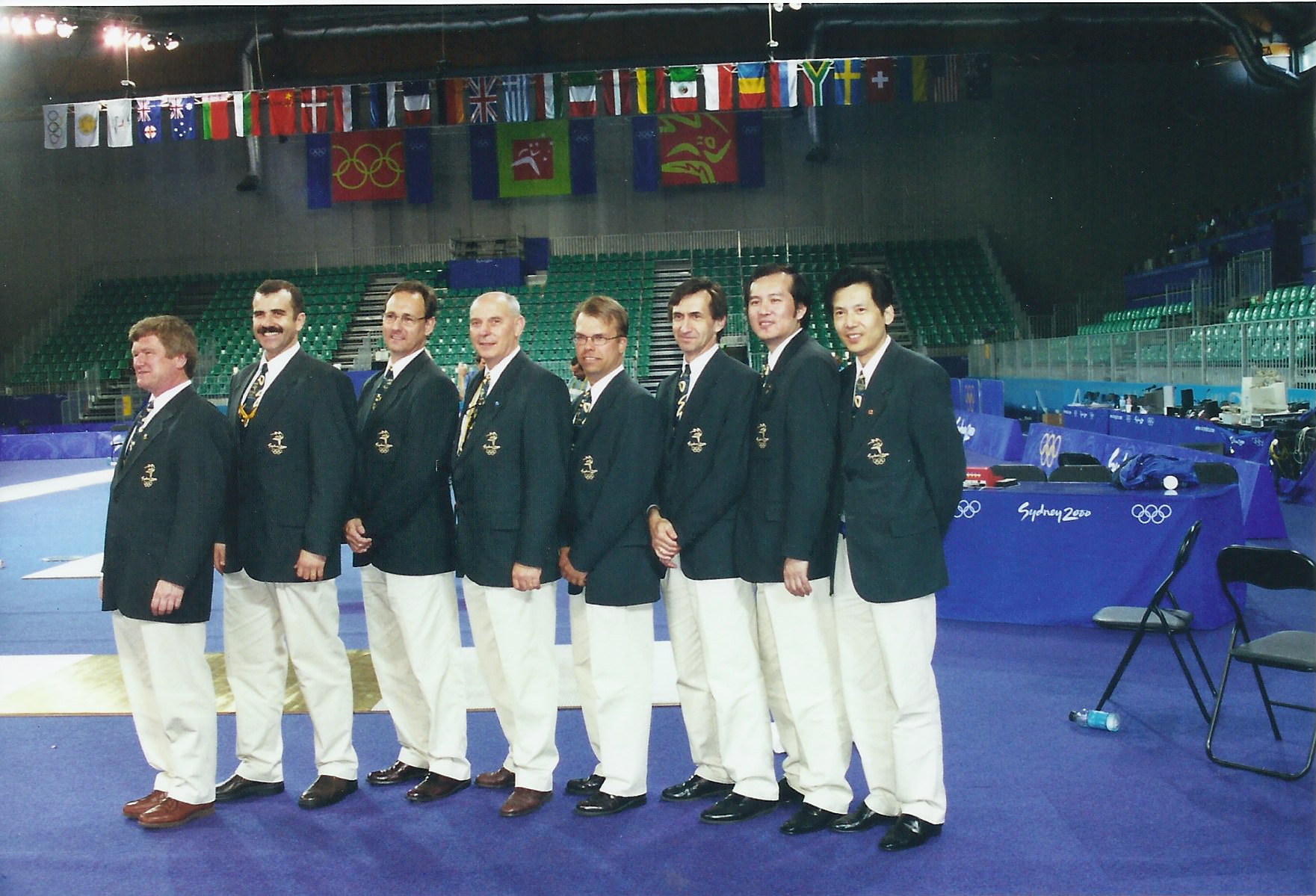

Sydney 2000 Olympics fencing officials with Australians Tony Dapre (first at left), Peter Osvath (third from right), Garrison Liu (far right)

(Supplied/ Bill Ronald)

Jeff says a big part of the Games’ success lay in getting the right people in the right jobs, so Bill could be confident things would be done properly. Robyn Chaplin, a South Australian fencer and past AFF President with a deep knowledge of the sport, managed international liaison. She flexed her finely honed people skills to fend off problems before they could reach Bill. Nandy Susic, a successful foilist from the 1950s who’d migrated to Australia from Europe some years earlier, brought multilingual calm to the warm-up area. “He made the European athletes all feel at home,” Jeff says.

Sydney 2000 Olympics fencing organising team

Back (L-R) Bill Ronald, Rob Otelli, Michael Reid, Alex Donaldson, Leon Thomas, Cate Purcell

Front (L-R) Mike Aiau Jeff Gray

(Supplied/ Bill Ronald)

Paralympics

After a short break, the same crew backed up to run the Paralympic fencing tournament in October 2000 at Sydney Olympic Park. The change in venue meant relocating all the sport infrastructure, another challenge for an exhausted organising team. “The Paralympics was the hardest event I’ve ever had to do”, Jeff says, not least because his wife had been diagnosed with breast cancer a few weeks earlier. Jeff picked her up from hospital in a SOCOG car following her mastectomy, settled her in at home, then returned to the fencing venue. “That was a day,” he says.

Legacy

Australian fencing didn’t gain a new venue or even equipment from the Sydney Olympics. But a legacy of tournament expertise and a greater emphasis on presentation and protocol has filtered into national events. Following the 2000 Games, Jeff made his own coloured pistes for use at later World Cups and the national Under 15 and Cadet championships held in Sydney.

“If you make the event look like an international, then it lifts the whole thing for the athletes, Jeff says. “It’s the same when you tell athletes they have to wear their state tracksuit for medal presentations. It changes their whole dynamic.”

Bill and his team had a grand vision for fencing at the Sydney Olympic Games and by all accounts the team succeeded, with the FIE and athletes showering Australia with plaudits. At a post-Games dinner to celebrate the event, the FIE declared the Sydney Games “the best ever”. FIE spokesman Jochen Faerber, quoted in the Sydney Daily Telegraph, said “We were all impressed with the different colours of the preliminary pistes. And the feedback we got from the athletes was that this was the best-run competition they had been a part of.”